Case Study: Gallardo v. Marstiller, 596 U.S. ___ (2022)

Earlier this year, on June 6, 2022, the United States Supreme Court issued its decision in Gallardo v. Marstiller, 596 U.S. ___ (2022). Because the case involved payments made by Florida’s Medicaid agency, there has been a whirlwind of questions and contemplation about how, if at all, Gallardo could impact Medicaid subrogation in Wisconsin. This article unfortunately does not offer a crystal ball to solve those concerns because the most honest answer at this point is, “we just do not know.” But by the end of this article, you should have a fundamental appreciation for the facts of and basis for the Gallardo holding, the current state of Wisconsin law with respect to Medicaid reimbursement, and some food for thought on what might happen next for personal injury practitioners with respect to Medicaid reimbursement.

Gianinna Gallardo was a 13-year-old student when she was struck by a truck after exiting her school bus in Florida.[i] She suffered catastrophic injuries and remains in a persistent vegetative state.[ii] Florida’s Medicaid agency paid $862,688.77 to cover Gianinna’s initial medical expenses following a $21,499.30 payment by a private insurer.[iii] Because of her permanent injury and condition, Medicaid continues to pay for Gianinna’s medical care.[iv]

The suit sought over $20,000,000 in damages but ultimately settled for just $800,000 and the settlement expressly designated $35,367.52 as compensation for past medical expenses (since $800,000 is just 4% of the claimed value, the designation for past medical expenses represented 4% of what had been paid by Medicaid).[v] Although no amount was designated, the terms of the settlement agreement did indicate that “some portion of th[e] settlement may represent compensation for future medical expenses.”

Factually relevant to the way in which the case made its way to the United States Supreme Court is that there is a presumption under Florida law[vi] that would have entitled the State to $300,000 of the settlement (37.5% of the gross settlement of $800,000 after deducting an amount representative of attorneys’ fees and costs).[vii] However, because the settlement included an allocation of just $35,367.52 for past medical expenses, Gallardo asked the State what it would accept to satisfy the Medicaid lien, but the State did not respond.[viii] Gallardo then held $300,000 in trust and filed an administrative proceeding to challenge the Florida presumption and ultimately filed a lawsuit arguing that Florida was violating the Medicaid Act by trying to recover portions of the settlement compensating for future care and of course the State took the position that it could seek reimbursement for payments for past and future care.[ix]

Ultimately, the supreme court held as follows:

Medicaid requires participating States to pay for certain needy individuals’ medical costs and then to make reasonable efforts to recoup those costs from liable third parties. Consequently, a State must require Medicaid beneficiaries to assign the State “any rights . . . to payment for medical care from any third party.” 42 U.S.C. § 1396k(a)(1)(A). That assignment permits a State to seek reimbursement from the portion of a beneficiary’s private tort settlement that represents “payment for medical care,” ibid., despite the Medicaid Act’s general prohibition against seeking reimbursement from a beneficiary’s “property,” § 1396p(a)(1). The question presented is whether § 1396k(a)(1)(A) permits a State to seek reimbursement from settlement payments allocated for future medical care. We conclude that it does.[x]

In justifying its holding, the supreme court provided a succinct summary, in its view, of the purpose of the Medicaid Act, including the Act’s “anti-lien provision.”

States participating in Medicaid “must comply with [the Medicaid Act’s] requirements” or risk losing Medicaid funding. Harris v. McRae, 448 U. S. 297, 301, 100 S.Ct. 2671, 65 L.Ed.2d 784 (1980); see 42 U.S.C. § 1396c. Most relevant here, the Medicaid Act requires a State to condition Medicaid eligibility on a beneficiary’s assignment to the State of “any rights … to support … for the purpose of medical care” and to “payment for medical care from any third party.” § 1396k(a)(1)(A); see also § 1396a(a)(45) (mandating States’ compliance with § 1396k). The State must also enact laws by which it automatically acquires a right to certain third-party payments “for health care items or services furnished” to a beneficiary. § 1396a(a)(25)(H). And the State must use these (and other) tools to “seek reimbursement” from third parties “to the extent of [their] legal liability” for a beneficiary’s “care and services available under the plan.” §§ 1396a(a)(25)(A)–(B). The Medicaid Act also sets a limit on States’ efforts to recover their expenses. The Act’s “anti-lien provision” prohibits States from recovering medical payments from a beneficiary’s “property.” § 1396p(a)(1); see also § 1396a(a)(18) (requiring state Medicaid plans to comply with § 1396p). Because a “beneficiary has a property right in the proceeds of [any] settlement,” the anti-lien provision protects settlements from States’ reimbursement efforts absent some statutory exception. Wos v. E. M. A., 568 U.S. 627, 633, 133 S.Ct. 1391, 185 L.Ed.2d 471 (2013). State laws “requir[ing] an assignment of the right … to receive payments [from third parties] for medical care,” as “expressly authorized by the terms of §§ 1396a(a)(25) and 1396k(a),” are one such exception. Arkansas Dept. of Health and Human Servs. v. Ahlborn, 547 U.S. 268, 284, 126 S.Ct. 1752, 164 L.Ed.2d 459 (2006). Accordingly, a State may seek reimbursement from the portion of a settlement designated for the “medical care” described in those provisions; otherwise, the anti-lien provision prohibits reimbursement. Id., at 285, 126 S.Ct. 1752.[xi]

That’s the Gallardo case and holding in a nutshell. So what will that mean in Wisconsin? Most practitioners agree that right now, we just do not know. While the language of the Gallardo decision certainly suggests a roadmap for how the Florida approach to reimbursement for paid and unpaid expenses could also apply here, it is also fair to trust at this time that the sky is not falling. I would suggest these takeaways be considered, which are in my opinion the most relevant to a personal injury practitioner’s review of how to address Medicaid liens moving forward:

- The Gallardo decision did not overrule Ahlborn. Although the Gallardo settlement allocated funds to compensate for past medical expenses, there was no allocation for future medical expenses and there was a presumption under the statute about the percentage reimbursement to be collected by the State. No similar presumption exists under Wisconsin law.

- There is no requirement based on Gallardo to do a Medicaid set-aside.

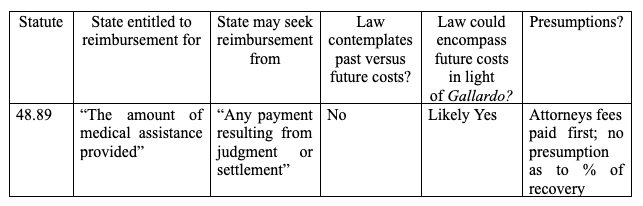

For quick reference, Wisconsin Medicaid reimbursement rights can be summarized as follows:

It is possible that the application of Gallardo in Wisconsin could or should be limited based on both the specific facts of the Gallardo settlement and the recovery presumption included in the Florida statutes. But there is also arguably a chance that because of how the majority interpreted the language of the Medicaid Act and the Anti-Lien Provision to allow for recovery of past and future medical expenses that the specific language in Wisconsin’s statutes (specifically “assistance provided”) will not matter.

One concern right now is what would happen if a Medicaid recipient recovered funds in a personal injury settlement but because of Gallardo, Medicaid was able to seek reimbursement for care not yet paid and then the beneficiary becomes disqualified for Medicaid benefits before any of the care is actually provided? The holding seems ripe for unjust outcomes but only time will tell how, if at all, the existence of Gallardo changes subrogation practice in Wisconsin.